By: Richard Van Heertum

This three-part series explores the demographic, political framing and outside influences that led Trump on the road to his unlikely victory. Included below is Part 2, which looks at political messaging and its important influence on Trump’s victory.

The Question

While Trump undoubtedly won the election due to his popularity among particular demographic segments, as explored in Part 1 of our election postscript, looking at demographics alone fails to dig into why his campaign appealed to those people. In Part 2, below, I explore how political framing and popular political sentiment aided Trump on the path to victory.

The Slogan

Before highlighting causes 6 through 10, I’d like to briefly discuss the brilliance and salience of Trump’s tagline “Make America Great Again.” Couched in these four words is really the essence of his campaign. Let’s start with the last word, “again,” which obviously denotes that America was once great. The interesting question, and one that Trump hinted at throughout the campaign, is when this greatness existed. As I’ll outline below, it appears to be a rather conservative and reactionary view of the past, where America was more white, more dominated by males, where minorities knew their place, isolationism reigned as the dominant foreign policy and there was limited immigration from non-European countries. Trump never said any of this explicitly, but it is largely implicit in the rhetoric he used throughout the campaign. And, as I noted in Part 1 of the series, that message resonated particularly with white Americans, particularly those mired in struggling economic conditions.

At the same time, “again” connotes that America is no longer great. This was at the heart of Trump’s messaging, framing a country in crisis that needed outside leadership to restore its former glory. Digging deeper into this section of the argument, the issues of violence, poverty and the threat of Muslim terrorists all emboldened many Americans to check his name in the booths.

Next, let’s turn to the first word “Make.” Here we get the policy prescriptions of Trump. First and foremost was the message that he alone could make America great again. The question that then emerged was how, and the answer provided by Trump is informative. First, he will eliminate the threat posed by Muslim terrorists and illegal immigrants taking jobs from Americans. Second, he will rollback our commitment to free trade and unfettered globalization, while placing the interests of America above those of our allies. And finally, and this might be most important, he will bring back the tax cut and deregulation policies of Ronald Reagan, a conservative hero who many forget left the office with a popularity rating teetering right around 50 percent and economic troubles that have persisted to the present day (e.g., rising deficits and national debt, growing poverty and increased economic inequality). These themes played well among rural white voters who are struggling economically and worried about the future of the country and, of course, among those in the middle and upper class who might be motivated by lower taxes and share a predisposition towards a rosy view of Reaganomics.

The third and fourth terms, “America” and “great” are also instrumental to Trump’s appeal. His ultra-nationalist rhetoric played particularly well in the heartland of America, where many feel that the country is changing in ways that challenges their idealized vision of the country. It also, indirectly, lays out the scapegoats to this process of making America “great” again. Among the most obvious are the “illegal immigrants” taking our jobs, the Washington elites screwing the average Joe and Jane, blacks through affirmative action, women through feminism, and Muslims through terrorism. Putting the four words back together, we see the when, why, how and what the Trump movement encompasses. The fact that one could make a strong case that these same rhetorical tactics have been employed by totalitarian regimes from Hitler and Stalin to Kim Jong-un and Putin, should maybe give us pause.

And now, on to five key results from the political rhetoric employed by both candidates.

1 – Change overrode other concerns

It is hard to call this a “wave election,” as the Senate and House were already in Republican hands, but it was certainly an election that seemed to hinge on the notion of “change,” not unlike that of Obama eight years ago. However, in this case the “change” was arguably to return to the past, given the general platform of Trump versus Clinton. Trump appears to want to return to the trickle-down economic policies of Reagan, to the isolationist Congress of the 1930s, to the deregulatory fervor of Clinton and Bush and to the racial backlash politics of George Wallace.

It is important to note that almost four in ten voters chose “can bring needed change” among four characteristics most important in the candidate they voted for, and 83% of those voters opted for Trump (to only 14% for Clinton). This may well be the most important non-demographic finding from the data, showing that voter discontent with Washington DC appeared to benefit the political neophyte over the establishment candidate. Clinton could not convince them that she would change things, particularly since she did little to differentiate herself from Obama, while Trump’s wide reaching repudiation of almost everyone in Washington appeared to resonate deeply with many voters.

Interestingly, Trump won 81% of the white evangelical or born-again Christian voters, better than the 78% that Romney garnered four years ago. When we consider this result, together with the white males (and to a lesser extent females) who made him president, we can probably rule out assuming that the change voters sought was in a progressive direction.

One final argument against the notion of a “wave” election was the reality that only 10% of voters were in the booth for the first time, and Clinton actually won those voters 56% to 40%.

2 – Clinton won on the economy, except where it mattered

The press has sold the story that Clinton lost because she failed to embolden white working class voters that were once the base of the Democratic party. There is certainly some truth in that, but Clinton actually won by 10% among the 52% of voters who said the economy was the most important issue facing the country.

Another point to be made, underreported by the media so far, is that Trump’s plans to cut taxes might have also appealed to people at the middle to top of the income ladder. His tax plan would give the richest 0.1% of families a tax cut of $1.3 million a year, cut the corporate tax rate from 35 to 15 percent and allow corporations to pay only $150 billion of the $700 billion in taxes they owe on the $2.5 trillion they have stashed overseas. That does not sound great for the average citizen, but Trump also wants to lower the top tax bracket to 25%, as it was under Reagan in 1986. The point is it appears many middle class and wealthy voters chose Trump at least partially because they saw it as in their best interests, either believing they would receive some tax cuts themselves and/or that changes in the tax code would spur economic growth and rising stock prices (a point noted briefly above).

The overarching point, however, appears to be that Clinton won the popular vote and among those most concerned about the economy, but not in the places most affected by the economic changes of the past 30 years – including in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, North Carolina and Florida.

3 – It’s the cynicism, Stupid

The thought that the election was decided by the ignorance of half of the electorate appears to be misguided. Sure, plenty of voters were ill-informed on the issues, others so jaded by the state of a American politics they stayed home (as noted above), but the cynicism at multiple levels appeared to play an extraordinary role in this election. To wit, a full 18% of Trump voters admitted they did not see him as fit to be president!

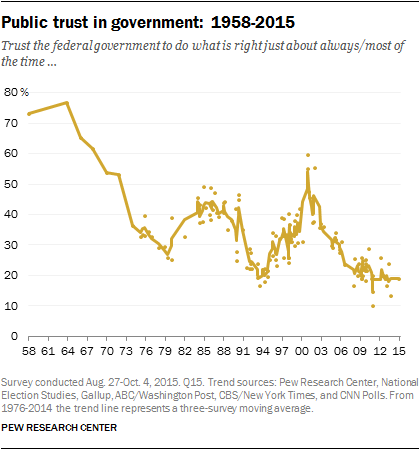

On the eve of the election, the Pew Research Center polled voters of each party to see how much they felt each candidate “has respect for democratic institutions and traditions.” Clinton fared better than Trump, with 62% saying she had a “great deal” or “a fair amount” or respect, to Trump’s 44%, but both had fairly large percentages of “not too much” or “not at all” – 37% for Clinton and 56% for Trump. The irony, of course, is that these numbers might have helped Trump, as respect for democracy appears to be fading dream of a bygone era. Trust in government has been on a steady decline since the mid-1960s, from a high of 77% in 1964, it has fallen all the way to approximately 19% today.1

Source: Pew Research Center.

Beyond that, Pew found that voters saw Trump as the most negative candidate since they began keeping these figures in 1988. Bush that year, Dole in 1996 and Kerry in 2004 were the only three candidates over the past 28 years to register above 50 percent, until Trump smashed the previous high of 53 percent (Dole) with his 62 percent. Clinton was a more “respectable” 44 percent, the highest among Democrats since Kerry in 2004, but the combined total shows that the public found the general tenor of the election “too critical,” without sufficient policy prescriptions to address the key issues affecting them. And yet, inexplicably, they found the less critical candidate to be the one less likely to solve those problems.

Looking at personal characteristics, less than half of respondents found either Clinton (49%) or Trump (25%) a “good role model.” The same was true of “honest” (Clinton 33%, Trump 37%), “inspiring” (42% and 35%, respectively) and “moral” (43% and 32%). 69% of respondents found Trump “reckless” (Clinton 43%), 65% said he had “poor judgment,” with Clinton at 56% and when asked if the candidate “was hard to like” both were well above 50% (Clinton 59%; Trump an astounding 70%). Finally, only 52% believed Clinton was a “strong leader,” and an even lower percentage (46) said the same of Trump. Collectively and individually, these results tell us that voters were uninspired and distrustful of both candidates, but that even with all the negatives, they decided Trump was the more likely to move the country in the right direction. This seems far afield of the intentions of our founding fathers and a rather profound indictment of the political system today.

Even worse, a full 58% of Clinton voters found it “hard to respect someone who voted for Trump” on the eve of the election and 40% of those who voted for Trump felt the same about Clinton. Those findings reinforce the political polarization so poisonous in America today and the way we have stopped listening to and talking to one another. Marshall McLuhan once argued that the opposite of violence was dialogue. One assumes the present state of political affairs makes violence a more likely outcome; as we have seen on numerous occasions over the past few years and more acutely since the election results came in.

Another way to quantify the level of cynicism was how many people didn’t even bother showing up this year. Turnout rates fell below those of 2008 and 2012 and returned us closer to the lower turnout seen for years before those two Obama victories. However, it is interesting to look a little deeper into those numbers. Turnout fell on average 2.3% in states Clinton won while remaining relatively stable in states that Trump won.2 Really, that summarizes the story of the election, with Trump able to take advantage of lack of enthusiasm among more progressive voters while his “movement” brought out just enough unreliable white voters to win.

4 – Backlash election, redux

Since the election of FDR, we could argue there have been three backlash cycles in American politics.

The first came in 1968, when Richard Nixon won the election speaking for the “silent majority,” who felt the cultural revolution went too far, while promising to get us out of Vietnam. Nixon started to roll back some of LBJ’s policies, but not to the extent that would follow in the wake of Watergate. The second backlash election came in 1980, when Reagan ran against not only The Great Society of LBJ but the New Deal of FDR. He cut taxes on income and capital, deregulated industry, finance and media and turned the country from the greatest creditor nation in the world to the greatest debtor nation. He also exploded the deficit and national debt by spending unprecedented amounts on National Defense.

One could then argue that Bill Clinton provided the third backlash cycle, but that would ignore the triangulation he employed to beat first George Bush (in a tight election possibly decided by Ross Perot) and then Bob Dole (by a sizable margin). Rather than shaking things up, Clinton largely continued the economic policies of his predecessors, even going as far as balancing the budget, shrinking the size of government and enacted reforms that further deregulated telecommunications and finance, cut the rolls of welfare, filled our prisons with minor drug offenders and set the stage for the financial crisis of 2008. George W. Bush provided a rhetorical alternative to the Clinton years with his “compassionate conservativism,” but that, too, failed to really challenge the status quo, except in cutting taxes dramatically, deregulating even further and getting us involved in a series of costly and, many would argue, unnecessary wars.

It was then Obama who gave us the third backlash election, in this case offering a progressive alternative to the politics of the preceding 28 years. Just as with Clinton, the Republicans ran against that agenda a mere two years into his first term and were then able to block most of Obama’s efforts over the past six years. With Trump, the continuing hunger for substantive change found its champion.

It is worth noting, in this regard, that Trump supporters did show themselves to be substantially less tolerant of others than Clinton voters, supporting the argument that his hateful rhetoric played well in certain circles. Pew found that Clinton supporters were substantially more likely to report a “great deal” or “fair amount” of respect for Muslims (69% to 28%), Immigrants (71% to 30%), Women (76% to 38%), Latino/as (66% to 35%), Blacks (67% vs. 42%) and “people like you” (57% vs. 49%). On the flip side, Trump supporters had more respect for whites (83% to 77%), Evangelical Christians (59% to 51%) and men (82% to 65%).

On top of this, only one in three voters thought the country was “generally going in the right direction.” Among those voters, Clinton won 90%. But among the two-thirds who claimed the country was “seriously off on the wrong track,” Trump took 69%. It is also worth noting that Trump was strongest where the economy was weakest, further backing up the point made in #3 from part I of this series. County-level voting did not vary much based on unemployment figures, but did on the share of a county’s voters who had “routine” jobs, including farming, manufacturing, other goods-related occupations and administrative, clerical and sales jobs. Where the percent of the county voters in these jobs was less than 40%, Clinton won by 35%, where it was 40% to 45%, by 15 points. However, when the percentage jumped to 45-50%, Trump won by about five points and among counties with over 50% of the jobs listed as routine, he won by 35 points.3 In places that are economically depressed, in other words, or where real concerns exist about their future economic prospects, Trump won big.

5 – Clinton ran a poor campaign

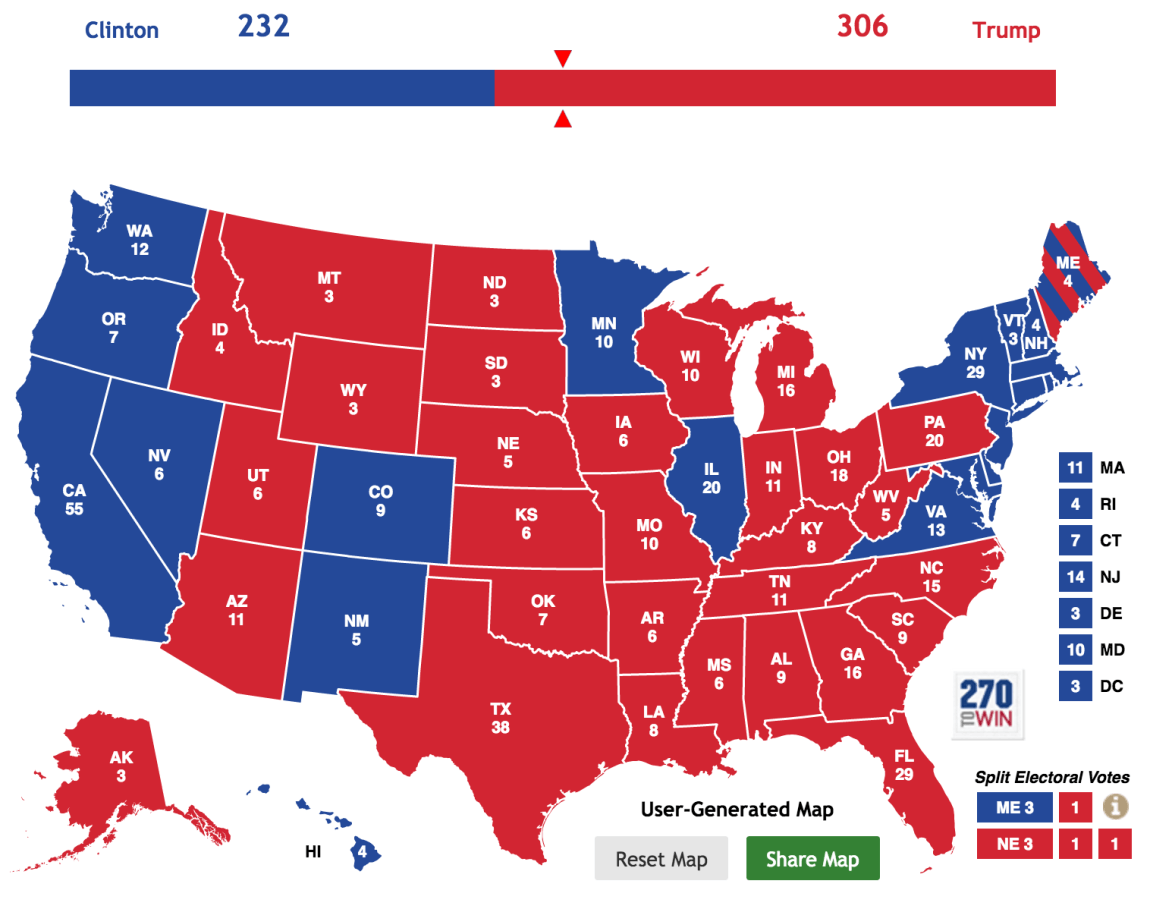

Looking at the 4 items above and the 5 from Part 1 of my Electoral postscript, it was still only one or two voters per 100 in a handful of states that gave Trump an unlikely path to the Presidency.4 Clinton won the popular vote handily and had a number of paths to the presidency, even with her poor overall showing. She could have won with Florida and Pennsylvania alone, with Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Michigan, with Florida and Ohio, alongside a whole host of other permutations that didn’t pan out as the panhandle of Florida started a string of upsets that sent Trump to the White House. However, it is worth noting how the findings above play into a general narrative on the election.

Americans are angry and want change. Clinton ran the campaign of a moderate whose major argument for the office was that she was “not Trump.” While that strategy proved effective for Obama in 2008, it is less effective when running against an unelected opponent, rather than one the people have already turned against, as they had with Bush by 2008. In fact, Clinton’s unwillingness or inability to truly differentiate herself from Obama may just have cost her the election. Don’t get me wrong, unlike Gore in 2000 – who made the mistake of first supporting the president in the Lewinsky incident and then failing to employ him in the campaign – Clinton tried to ride on the coattails of Obama’s popularity (around 54% at the time of the election). The problem was that she spent more of her time denouncing Trump, without really telling the country how she would move us forward. Anyone who saw the majority of campaign ads by Clinton knows this to be true, as they all seemed to be negative attack ads on Trump rather than calls for positive change.

Electoral map by 270toWin.com.

It appears that Clinton was seen by many as a crooked and aging member of the old established elite who wasn’t that different from Trump since leaving the White House, accruing with her husband a fortune that is estimated to be over 200 million dollars. She stands for exactly the sort of personality many parts of the country are tired of hearing promises from that rarely come to fruition. She is the elite East Coaster who is trying to tell them how to live their lives while failing to improve the quality of those lives. She is just the sort of politician who, they believe, says one thing and then does another. She fits the narrative of a political elite who are liars, crooks and cheats – even if most of that narrative has proven rather difficult to find hard evidence to support. Her unpopularity apparently made it easier for many to simply stay home and for others to place their faith in the less known commodity of Trump.

Obama reinforced this notion that Clinton was seen as remote by Middle America in comments Monday, saying he won in Iowa, a mostly white state, not because “the demographics dictated it,” but because he spent 87 days going to “every small town and fair and fish fry and VFW Hall” possible. He intimated that Clinton failed to do the sort of on the ground campaigning necessary to win elections, relying too much on a national press strategy he believes is “increasingly difficult” to use as a route to victory.5 Clinton only visited the state Obama won four times after the primaries and completely ignored Wisconsin, allowing that state to turn red for the first time in almost 30 years. She spent less time on the stump than any recent candidate in history and placed her efforts in winning North Carolina, a state Obama lost four years ago, and Pennsylvania, which she still lost for Democrats for the first time since 1984, rather than the other swing states that could have won her the election. In total, Clinton held substantially fewer campaign events than Trump and, at least according to most estimates, tended to have smaller crowds for those events.

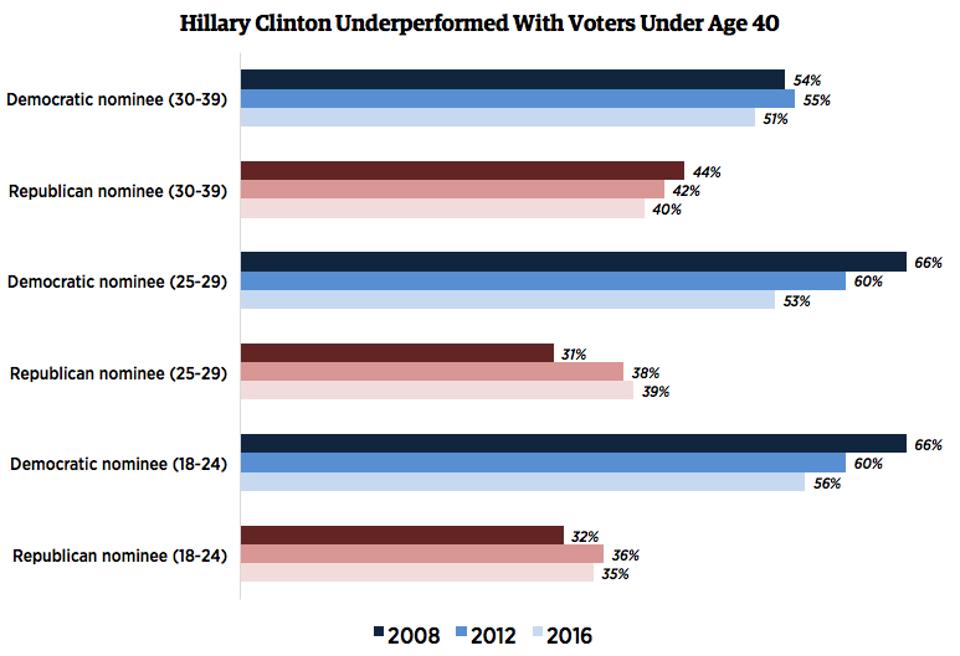

A final big difference between Obama and Clinton was their differential ability to get out the young vote. Obama set records among millennials, galvanizing them to vote at record numbers. Clinton saw a drop-off compared to 2012 and 2008, although the missing voters didn’t defect to Trump (who performed similarly to McCain and Romney), as many either did not vote at all or turned to third party candidates.6 This proved particularly problematic, as the average Republican voter is getting older while Democrats get younger. According to Pew, the GOP (once more youthful than the Dems), has aged rapidly over the past 24 years, with 58 percent of Republican voters 50 or older, compared with 38 percent in 1992. Among Democratic voters, 48 percent are 50 or older, compared with 42 percent in 1992.7 Both parties are aging, but the Republicans much more steeply than Democrats. In the long run, this bodes well for the Democrats, but with so little power at any level of government, one wonders how they will embolden the next generation to get involved again.

Youth Vote in 2008, 2012, and 2016. Chart by Forbes.

Youth Vote in 2008, 2012, and 2016. Chart by Forbes.

Even turning to the debates, which most pundits thought she won handily, the public at large apparently disagreed. Among the 64% who said the debates were an “important” part of their vote, Clinton only won by a narrow 50% to 47% margin over Trump. Of the 82% who said the debates were a “factor” in their decision, Trump actually won 50% to 47%.

Overall, it appears Clinton thought victory would be simple and thus failed to work hard enough to ensure that victory. She campaigned less than Trump, scorned the opportunity to provide a positive message to galvanize the base or young voters, neglected to capture the imagination of enough women and progressives with the thought of a first female president, omitted to deliver a coherent message on where she wanted to take the country over the next four years and failed to take the Trump movement seriously. More than anything, she was unsuccessful in convincing enough Americans that Trump was truly dangerous to our future and that she would take the steps necessary to improve the quality of life of the many Americans who continue to suffer in the new globalized, post-Fordist America of today.

It is worth noting that the road to Clinton’s loss was partially paved by Obama’s presidency as, over the past eight years, Democrats have lost almost a thousand state-legislature seats, a dozen gubernatorial races, sixty-nine House seats and thirteen in the Senate. Last Tuesday didn’t come out of nowhere, though Clinton arguably played a large role in her own defeat.

1 Pew Research Center, “Beyond distrust: how Americans view their government,” 23 November 2015.^

2 Carl Bialik, “Voter Turnout Fell, Especially In States That Clinton Won,” The FiveThirtyEight, 11 November 2016. ^

3 Jed Kolko, “Trump Was Stronger Where The Economy Is Weaker,” The FiveThirtyEight, 10 November 2016.^

4 Nate Silver, “What A Difference 2 Percentage Points Makes,” The FiveThirtyEight, 9 November 2016.^

5 Francesca Chambers, “Obama’s pointed rebuke to Clinton for election loss as he tells how HE won by going to ‘every fish fry’,” The Daily Mail, 14 November 2016.^

6 Avik Roy, “A Big Part Of Hillary Clinton’s Defeat: She Alienated Millennial Voters,” Forbes, 9 November 2016.^

7 Pew Research Center, “The Parties on the Eve of the 2016 Election: Two Coalitions, Moving Further Apart,” 13 September 2016.^

No Comments on "Election postscript: Making political framing great again"