By: Scott Baptista

Chocoholics take heed! The issues we’re experiencing with the chocolate supply chain has just as much to do with people as it does with climate change.

As detailed in part 1, an increase in global temperatures and the subsequent rise in the number of attacks by fungi and other pests are reducing the production of the cocoa beans necessary to make chocolate delicacies. Though companies like Hershey and Mars are partnering with the World Cocoa Foundation1 to sponsor various farmer training sessions to aid and educate local farmers on how to adapt to the changing climates, these training sessions do very little to alleviate another of the endemic issues at hand, poverty.

Make Chocolate Fair,2 the European campaign for fair chocolate, explains that, in 2014, the total global retail sales of chocolate confectionery reached $100 billion for the first time in history, while at the same time, many cocoa farmers and workers found themselves working for less than $1.25 per day. In such a situation, when every hand matters, child labor flourishes. Whether because children are tasked with helping their family on the farm, or they are enlisted to help their family earn enough to survive, the end result is still the same. To give an example of just how wide spread this practice is, during the 2014-2015 harvest season,3 Côte d’Ivoire employed an estimated 1,203,473 child laborers ages 5 to 17 within the cocoa supply chain. This is not a system that will just disappear on its own. Even with companies like Nestlé4 interacting with various rural communities to avoid child labor, it will take a long time to fully abolish it. Worse, the cocoa economy itself seems to moving in the opposite direction.

Simply put, the value of the cocoa bean itself is falling. If the supply chain solely consisted of bean producers and chocolate makers, monetary exchanges would mostly reach an equilibrium. That said, the higher prices in today’s chocolate are typically used to subsidize research and development, marketing distribution and other activities while the price for the cocoa beans themselves have, ironically, stayed stagnant.5 In essence, farmers today have less influence over the economy of cocoa than their predecessors. Many farmers, as a result, have become disillusioned with their prospects and the difficulty in cultivating cocoa bean, and are turning to other crops, like rubber, or moving to cities to find work and a better future. And while completely understandable, such actions have exacerbated the situation by reducing the overall production of the beans.

Adapting economics

Due in large part to the decrease in cocoa bean production (whether because of a shifting climate, increased attacks by pests or farm abandonment), and the subsequent rise of prices, companies like Hershey and Lindt find they need to search for other avenues to keep their profits up. To show you what I mean, while a ton of cocoa cost $1,813 (adjusted to 2015 dollars due to inflation) a little more than 10 years ago, in 2015, a ton of cocoa cost double that, $3,244.6 Such a jump in price was especially felt the year prior where numerous chocolate makers raised their prices about 8 percent, in an attempt to stay competitive and profitable.

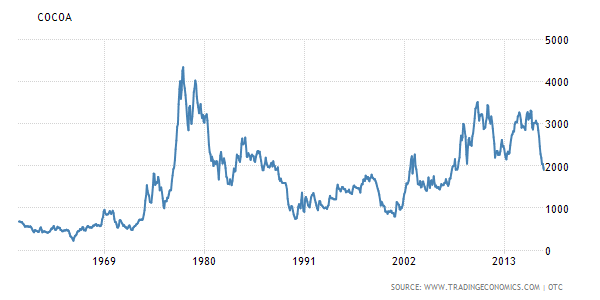

This doesn’t mean that prices are increasing non-stop, however. On April 27, 2017, for instance, cocoa traded at $1,876.7 Simply put, there is a general, overarching trend towards increasing prices. This is especially apparent when the data is taken historically. For example, throughout 1969, cocoa was being traded from prices, adjusted for inflation, varying from just under $1,000 to a little over $800, while in 2006, the price was just about $1,500.8 Moreover, such a trend isn’t necessarily isolated to cocoa. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the trading prices for the Food and Beverage category in the US are going up just as well.

However, as you can see below, cocoa is increasing in price much more rapidly than the overall CPI for food and beverages.

In either case, as opposed to what you might think, corporate price hikes don’t seem to “trickle down”9 to the farmers themselves. As previously stated, cocoa farmers who depend on the amount of beans produced to make any money, find themselves at the bottom of the food chain. Retailers and middlemen (exporters, research and development staff, marketing employees, traders, etc.) are paid first.10 Thus, the asymmetry in the system is propagated. To offset the rise of cocoa prices, for instance, Jacques Torres11 explains that, “…planters are trying to find [a] way to produce more. The problem is that, by planting more, we find new hybrid of cocoa. By doing that we lose some quality. So the price of the very high end chocolates rise even more.” Though no major chocolate brands have announced additional price hikes for this year, since the price of cocoa has been steadily increasing over time, sooner or later, another price hike will come.

To break the cycle of poverty

The cycle of poverty, however, can change. Especially since doing so is beneficial for both the economic sustainability of the governments and chocolate makers that produce the chocolates we all consume. Besides training sessions, reform12 in Côte d’Ivoire’s chocolate industry is providing farmers with a guaranteed steady price for cocoa beans (approximately $1.50 per kilo of cocoa beans).13 To do this, the government of the Côte d’Ivoire has created a marketing mechanism that involves the forward sale of 70-80% of the next year’s crops through twice-daily auctions, the process of which is enforced by the Conseil du Café-Cacao which was created in 2012. These forward sales auctions allow the establishment of a benchmark price for the next crop year and ensures a guaranteed minimum share of 60% of the CIF (cost, insurance, freight) price to farmers.14 Nestlé’s Research and Development Department is, furthermore, producing genetically modified cocoa to produce higher yields and greater resistance to diseases and pests. In fact, they’ve committed themselves to not only give away 12 million of these genetically modified trees to cocoa farmers by 2022, but to also invest in the education system (building schools, investing in good teachers, buying school equipment, etc.) of cocoa producing nations.15

Cargill buys 20% of all beans produced in the Côte d’Ivoire, mostly from various farmers groups called co-operatives, and turns the beans into components that will eventually produce chocolate (e.g., cocoa powder, butter, etc.) before transporting them to the chocolate makers themselves. As it turns out, they work very closely with the co-operatives they buy from to ensure their cocoa beans become certified, and stamped with the approval of the Fair Trade Foundation, the Rainforest Alliance and UTZ.16 Certification, in essence, shows that farmers have grown their cocoa under strict standards, and have not used child labor. And yes, such regulations may be daunting to many farmers, most of which run small scale farms and expect their kids to help out, but there’s a very real incentive for becoming certified. Farmers get a higher market price and a bonus premium on top, up to $200 per ton, both of which go a long way in supporting their business (i.e., allows them to purchase equipment, hire helpers, etc.). Furthermore, more than 1/3rd of what manufacturers pay for certified cocoa gets invested back into farmer training programs.17 And the good news doesn’t stop there. While about 20% of the beans sold today are certified, several of the large manufacturers (Mars,18 Hershey,19 etc.) have gone so far as to commit themselves to sourcing 100% certified cocoa beans by 2020.20

This is not charity on the part of massive corporations. Ensuring that cocoa beans produce higher, more disease resistant yields, and that there are enough farmers to harvest them makes sure that there is enough cocoa in the future to sell. Chocolate, after all, is a business.

We as consumers have the power to influence better farming practices throughout the globe as well as the prosperity of the cocoa farmers themselves. We can strive to buy chocolate made from certified beans, invest in the education system of the countries most known for producing chocolate (Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, etc.), have more of an understanding of what is actually being purchased (i.e., understand what it takes to make the products purchased, like chocolate with higher percentages of cocoa), and invest in the organizations that help train, educate and incentivize cocoa farmers worldwide (Fair Trade Foundation, The Rainforest Alliance, UTZ, etc.).

Everyone, if possible, should enjoy the deliciousness that is chocolate and support its production, but nothing should be taken for granted for the possibility exists that in a not-so-distant future, only the wealthy will be able to afford cocoa-based products. That is, unless we help the supply chain become sustainable from its beginnings to its end.

Because an unsustainable chocolate economy means no chocolate for you. And no one wants that.

1 Hannah Furlong, “Hershey, Lindt, Mars, Nestlé Join New Program to Help Cocoa Farmers Adapt to Climate Change,” Sustainable Brands, 2 June 2016.^

2 “Cocoa Prices and income of farmers.” October 26, 2015. Make Chocolate Fair! Retrieved from http://makechocolatefair.org/issues/cocoa-prices-and-income-farmers-0 ^

3 Department of Labor https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor/c%C3%B4te-dIvoire ^

4 Richard Quest. March 4, 2014. Cocoa-nomics – CNN FULL Documentary. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yWiK7gNBUmQ ^

5 Antoine Fountain in an interview with CNN’s Richard Quest. “Cocoa-nomics: CNN FULL Documentary,” CNN, 4 March 2014. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yWiK7gNBUmQ ^

6 Peter Gillespie, “Chocolate lovers: prices could go up (again)!” CNN Money, 23 June 2015. http://money.cnn.com/2015/06/23/investing/chocolate-cocoa-prices-go-up/ ^

7 Trading Economics. 4 April, 2017. (http://www.tradingeconomics.com/commodity/cocoa ^

8 Ibid. ^

9 Investopedia. 2017. Retrieved from: http://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/trickledowntheory.asp ^

10 Richard Quest. March 4, 2014. Cocoa-nomics, CNN. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yWiK7gNBUmQ ^

11 Jacques Tores in an interview by CNBC’s Erin Barry. “Chocolate lovers send demand, prices soaring: Retailer,” 26, March 2016. (http://www.cnbc.com/2016/03/24/chocolate-lovers-send-demand-prices-soaring-retailer.html) ^

12 Agritrade. December 16, 2012. Retrieved from: http://agritrade.cta.int/en/layout/set/print/Agriculture/Commodities/Cocoa/Special-report-Cote-d-Ivoire-s-cocoa-sector-reforms-2011-2012 ^

13 Quest, Cocoa-nomics. ^

14 Agritrade, Special report. ^

15 Quest, Cocoa-nomics. ^

16 Cargill. 2017. Cocoa Certifications” Retrived from https://www.cargill.com/sustainability/cocoa/cocoa-certifications ^

17 Ibid. ^

18 Mars Incorporated. 2017. Retrieved from http://www.mars.com/global/sustainability/raw-materials/cocoa ^

19 The Hershey Company. 2017. Retrieved from https://www.thehersheycompany.com/en_us/responsibility/good-business/responsible-sourcing.html#tab3 ^

20 Quest, Cocoa-nomics. ^

No Comments on "The chilling future of chocolate: Breaking the cycle of poverty and child labor"