By: Rich W. Sharp & Patrick Zimmerman

There is a general assumption that numbers are precise. Because of math or science or number fairy dust or something.

Numbers are great. Data helps us express measurements, which then lets us compare things, evaluate them, analyze them, and the like. Without numbers, there would be no listicles; the Internet would cease to exist. It’s also handy for saving the world.

Sure, we know we should be careful about who’s peddling what when it comes to analysis. “Lies, damn lies, and statistics” after all. But how often do we stop to consider the numbers themselves? It’s only recently, in our brave new alternative-fact world, that there have been open attacks on the data itself instead of the analysis or the analyst. Questioning a reporter’s subjective telling of a tale is something we do instinctively, but we also need to question what we unwittingly hold to be objective: the means, methods, and opportunity applied to data collection.

The problem is that people don’t spend nearly enough time thinking about how any given datum is produced. They do not materialize out of the ether onto page and screen, but are recorded, by people or machines (that are designed and built by people, my friend), and those come with some degree of error (intentional or unintentional). Once turned into “cold hard numbers,” that error tends to be lost. For example:

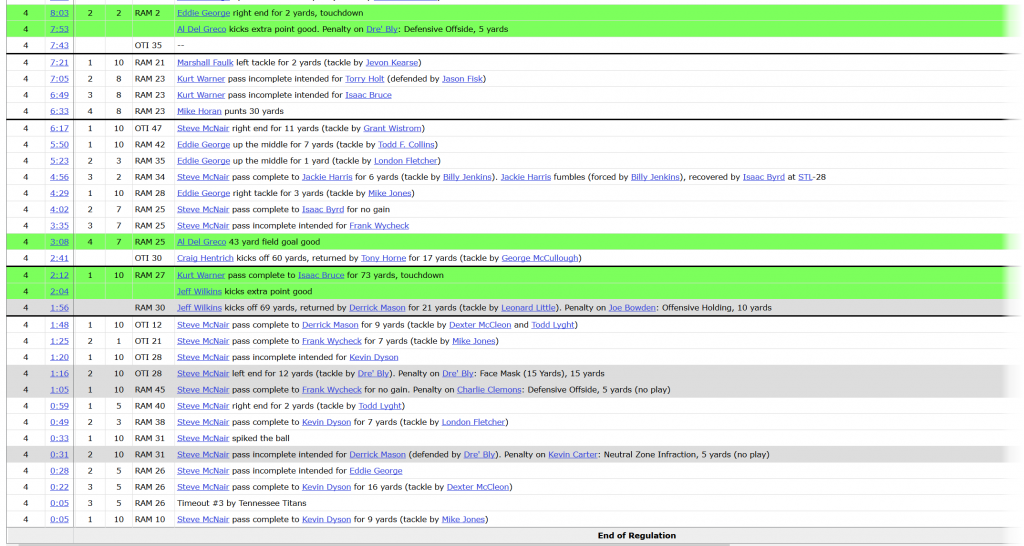

No, we did not pick that game as an example by accident.

A number in a big-ass table is fundamentally disconnected from the recording process. Most sources will require someone to look at a footnote, follow a link, or flip to another page entirely for the methodology behind that datum’s collection. Understanding how a recording is produced allows you to understand its level of certainty. See any error bars or sig figs in that table? Neither do we.

Why does this matter? Because numbers affect decisions about policy and strategy. Erroneous certainty about data leads to (incorrectly) inflexible or expansive decision-making.

Some illustrative examples

-

- The park ranger

-

The inspiration for this piece came when the Puncertain crew took some time out to climb a few pyramids in México. A very friendly park ranger stood on one of the terraces of the Pyramid of the Sun (or maybe water. It’s unclear.), assisting visitors up the steep steps, giving guidance, and corralling over-ambitious wayward 6 year-olds….all while clicking away at a tally counter in one hand. At one point, our (friendly, personable) ranger finished off a 30-second burst of frenetic mashing, looked down at the tally, then took off for parts unknown.

“Who cares whether the count was accurate or not?” you, dear reader, may wonder.

That number will go down in a report about attendence figures, which then becomes an immutable and trusted número, puro y duro. That number then is used to factor visitors into budget allotments to run the park, service estimates for the city surrounding it and the transport lines servicing the tourist trade (domestic and foreign), and potential future development of the park (continued excavations, funding for study, expanded visitor centers, and the like). Also, visitor traffic is taken to account in the terrifyingly scientific-sounding UNESCO world heritage site Threat Intensity Coefficient.

It’s a coefficient! Extra science points!In a word: money. How is UNESCO’s Threat intensity coefficient determined? In part, due to foot traffic data that originates with a dude in a nice hat (or a bunch of chapeaued dudes) who may or may not hit that tally clicker for the same reasons that the UN thinks he does. That’s why knowing how and why numbers are produced and applying the proper level of uncertainty to quantitative as well as qualitative datasets is critical.

-

- The park ranger

-

- The first down

-

As illustrated by the Super Bowl XXXIV example above, Kevin Dyson came a yard short of a (potential) game-tying touchdown on the final play of the game. Drama, and one of the best sports photos ever. However, the Air McNair Titans came thiiiiiissss close, with that distance based on a series of educated guesses by the guys in the zebra suits. While most sports have some judgement calls (balls and strikes, anyone?), American football is one that goes furthest out of its way to hide the inherently inexact nature of ball-spotting, including an elaborately choreographed dance of pseudo-precision.

Basically, football yardage chains fail significant figures forever. Even if we’re generous and grant NFL-quality referees an average accuracy of ±1ft (obviously, a ball held out by a player stretching for a first down is easier to spot than one in the middle of a dogpile), rulings based on chain measurements are treated as if they were accurate to within about an inch.

Related: ridiculous product of the year award…

LASER CHAINS! Held at a right angle by eyeballing the sideline paint (by a disembodied hand: human error has been eliminated).

-

- The first down

-

- The box office record

-

Something shocking happened last year. Total annual box office receipts were down for the first time in since, like, forever. It’s supposed to be easy to write the annual state of the industry article. You just dust off the headline template and fill in the blanks: “20__ Box Office Revenue hits $_____.__B for Another Record Breaking Year.”

Of course, that’s if you’re pitching the movie business to new investors. If you want to get copyright law extended or crush your streaming video competition, you bust out the alternative truth for the congressional hearing: “Domestic movie theater attendance hit a ___ year low in 20__.” So are the studios victors or victims? Where do these numbers come from?

Source: National Association of Theatre Owners. Mouseover for details.

We’re glad you asked. Seems pretty straightforward, right? You just add up all the ticket sales. And yeah, that’s how we get about 90% of the answer a week after you read the article about the box office top 10. Two firms, Rentrak and Nielsen, feed the raw data from the roughly 90% of theaters they cover back to the studios. But those aren’t the numbers that get released in the papers. The studios self-report estimated results for the movies they made. The estimates are used to make up for the missing portion of theaters and to get a jump on sales that are still in the pipeline (there are some weekend tickets that haven’t been tallied by the time the Sunday evening or Monday morning list is going to print).

Interesting filter there, inserting studio estimates in place of cold hard numbers from counting cold hard cash. Fortunately, there are a couple mechanisms to keep them honest: contracts tie actor or director pay to box office performance are a penalty for inflated claims, and the SEC always has an interest when public companies like Disney start making their financial performance public.

-

- The box office record

Ok, so what can we do differently?

Read the footnotes. Strive for clear statements about uncertainty when working with your own data. A number is an abstracted piece of information and, as such, should encode exactly the amount of precision used in its creation. Think critically about methodology.

Basically, think (alternatives: burn up in the Martian atmosphere, drive off a cliff, allocate congressional districts, …).

No Comments on "On the origin of data"