By: Scott Baptista

Chocoholics, beware! The chocolate shortage everyone was talking about for the past few years may be closer than you think.

The times, they are changin’

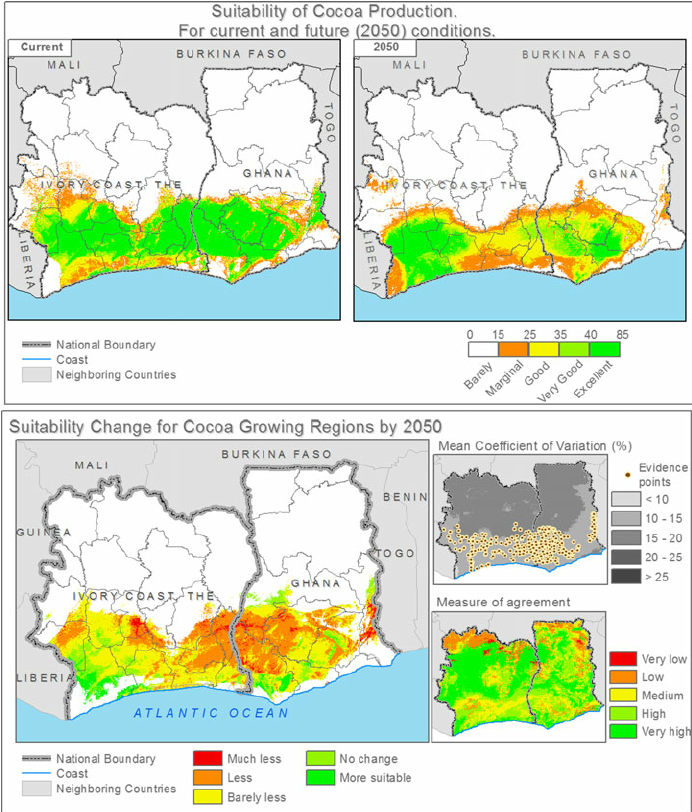

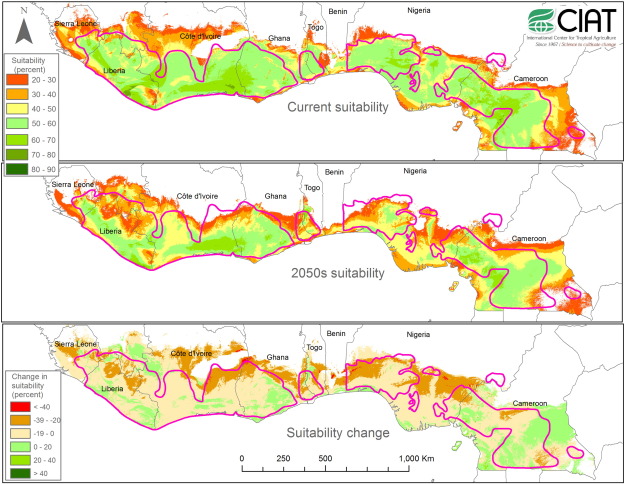

Climate change may prove to be a greater threat to the production of cocoa than anything the chocolate industry has faced thus far. Cocoa trees (Theobroma cacao, Criollo cacao, Forastero cacao, and Trinitario cacao)1 grow in tropical climates and thus need a lot of rainfall and hot, humid weather to prosper.2 Global warming, as you probably surmised, isn’t the biggest problem; water (as usual) is the limiting factor for cocoa trees.3 This effect can already be felt today. In 2015, both West Africa and Ghana were experiencing deep enough periods of drought (atop continued attacks by the various fungi that infest cocoa pods)4 that their production of cocoa was seriously affected.5 The International Center for Tropical Agriculture projects that areas to the margins of Ghana’s production belt (Southern Brong Ahafo, Northern Ashanti, and the North and South of Volta) will be classified as no longer suitable for cocoa production by the 2050s due to long periods of low precipitation and strong dry seasons (i.e., low humidity and soil moisture).6

Current and future (i.e., the 2050s) climatic suitability predictions for cocoa production within cocoa-growing regions of Ghana and Côte d ’ Ivoire.7

Climate suitability change for cocoa production within cocoa-growing regions of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire.8

Demand-side cocoanomics

The demand for more chocolate is only making production problems worse for the industry, exponentially in this case. Though Europe and North America still account for more than half of global chocolate sales (a percentage that’s still increasing),9 demand in emerging markets, especially in China and Latin America, is forecasted to grow over the next five years by 23 percent and 31 percent, respectively. These numbers may not sound like such a big deal, but consider that in 2013, people world-wide ate roughly 70,000 metric tons more cocoa than was produced.10 But it’s more than just more people wanting more chocolate that’s causing an issue, but also the type of chocolates they crave. The demand for high quality and dark chocolate has played a heavy contribution, especially since both take more cocoa to make than the average chocolate bar. To be more precise, while milk and white chocolates contain about 10% to 20% cocoa respectively, darker varieties can contain more than 70%.11 No matter how you look at it, these numbers are a bit intimidating.

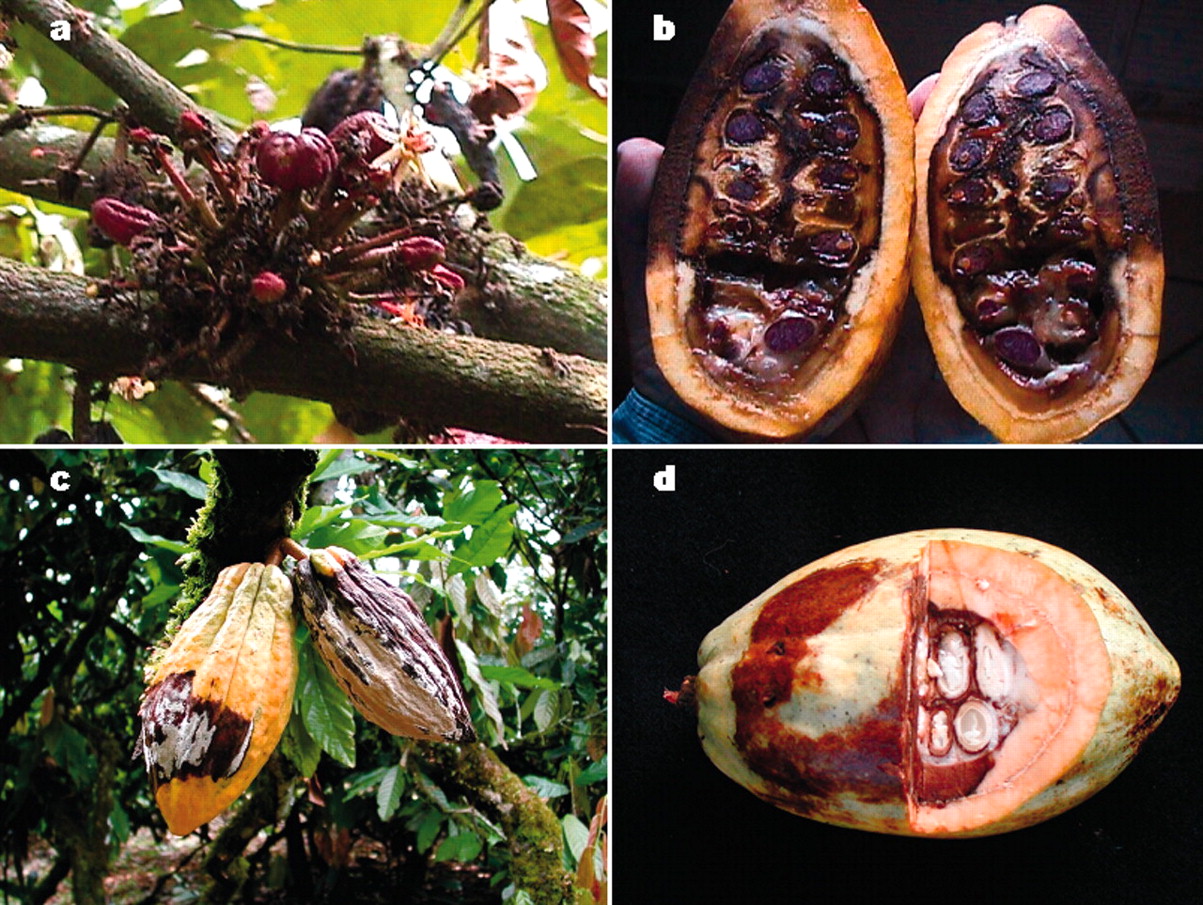

The issue, however, is far more complicated than less chocolate being commercially available. For instance, the bulk of cocoa bean production, though grown in tropical climates all over the world, comes from small, family-run plantations in West Africa.12 These small-scale productions tend to be unable to afford pesticides, better farm equipment and adequate labor. Furthermore, since they tend to be isolated farms, there is generally little communication or coordination between them, making it that much more difficult for farms to survive once something goes bad. As such, the industry as a whole becomes increasingly more vulnerable to bad weather (such as droughts, or excessive rain), various pathogens, and pests. In fact, some of the diseases in West Africa can “…wipe out an entire farm if it’s not well taken care of.”13 To illustrate just how dangerous some pests and diseases can be (especially Witches Broom, Frosty Pod Rot, Mirids, and Cocoa Pod borer), the International Cocoa Organization (ICCO) estimates global losses of cocoa beans to pest at around 30 to 40 percent in 2015.14

a. Witches’ broom infection of plant stems caused by Moniliophthora (Crinipellis) perniciosa b. Chocolate pods and beans infected with M. perniciosa c. & d. Frosty pod rot caused by Moniliophthora roreri.15

The bottom line

Even if the Paris accords16 were signed and enforced by every single country on the planet, global temperatures would continue to rise for decades (at least).17 So the industry will be dealing with a more challenging production climate (literally and figuratively) while I can’t see chocolate becoming unpopular any time soon. But don’t despair just yet! Some progress is being made in resolving these issues due to efforts made by partnerships between the World Cocoa Foundation and companies such as Hershey and Mars. These partnerships18 are currently sponsoring various farmer training sessions to aid and educate local farmers on how to adapt to the changing climates (including research and development into climate resilient and higher bean yielding cocoa trees, improved farming practices, and education focusing on deforestation). These trained farmers are then tasked with consulting other farmers and advising them on farming and pest control techniques. This not only helps farmers gain better control over what’s happening to their own plots of land, but helps the overall industry adapt to the changing environment.

While chocolate production is currently in a state of flux, there are practices (discussed in the next installment) that people worldwide can follow to prevent any long lasting and disastrous effects. The important word there is “flux.” Chocolate isn’t about to disappear from the shelves of any grocery store, especially since chocolate companies everywhere are striving to protect future business.

What’s next?

What’s actually at stake, besides the worldwide increase in prices, is a reduction of just how much cocoa beans can be harvested at any point in time, and all the consequences that will bring to those who farm them. Training sessions, while on the right path towards creating a sustainable supply of cocoa, do very little to alleviate the endemic issue at hand, poverty.

But let’s continue that discussion on another day, especially since poverty not only exacerbates the various natural issues hampering cocoa production (climate change, diseases, pests, etc.), but also keeps bad practices in play (i.e., child labor, lack of knowledge on how to deal with pests, etc.). Part 2 of this series will not only delve into how near non-existent wages influences the various labor practices of cocoa farmers, but it’ll show just how much influence the economics of cocoa production plays in their lives and ours.

For now, just remember that while cocoa production is taking place in areas you may believe are a long ways away from home, what happens there can still be felt all over the world, even if it’s just through the increase in the price of a chocolate bar.

1 “Barry Calebaut. “Theobroma cacao, the Food of the Gods.” 2016.^

2Ibid. Cocoa trees need a consistent temperature of 25-27°C (77-81°F) and regular rainfall between 1250-2500mm per year. Direct sunlight and strong winds further hamper the growth of these trees. ^

3 Michon Scott, “Climate & Chocolate. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. 10 February 2016. ^

4 A few fungi, like the White thread blight, persist in drier weather, but cannot stand temperatures that are too cold or dry. University of Horticultural Sciences, Bangalkot, “Pest and Diseases of Cocoa” 21 September 2012. Arathi, “Safeguarding The Future of Chocolate,” Youngzine, 9 February 2015.^

5 Stephanie Findlay, “World’s Chocolate Supply Under Threat from Drought in Ghana and Nasty Fungus,” The Telegraph, 4 May 2015.^

6 Christian Bunn et al., “Bittersweet Chocolate The Climate Change Impacts on Cocoa Production in Ghana,” International Center for Tropical Agriculture, 18 December 2015.^

7 Läderach, Martínez-Valle, et. al, “Predicting the future climatic suitabilityfor cocoa farming of the world’s leading producer countries, Ghana and Côted’Ivoire,” Climatic change 118, No. 2, August 2013: 841-854.^

8 Götz Schroth et al., “Vulnerability to climate change of cocoa in West Africa: Patterns, opportunities and limits to adaptation,” Science of the Total Environment 556, June 2016: 231-41.^

9 AP, “ Why Chocolate Prices are Set to Rise,” CBS Money Watch 30 October 2014.^

10 In 2013, Earth produced (gross production) around 4.104 million tons of cocoa beans. Therefore, it consumed about 1% more chocolate than it could produce. Jean-Marc Anga, “The World Cocoa Economy: Current Status, Challenges and Prospects,” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 10 April 2014.^

11 Roberto A. Ferdman, “Your Dark Chocolate Addiction is Driving Up the Price of Chocolate,” Quartz.^

12 AP, “Why Chocolate Prices are Set to Rise.”^

13 Sona Ebai, World Cocoa Foundation’s (WCF) Chief of Party in an interview with CNN’s Richard Quest. “Cocoa in West Africa – Short Documentary,” CropLife International 3 November 2014.^

14 “Pests & Diseases,” International Cocoa Organization, 10 April 2015.^

15 MC Aime and W. Phillips-Mora, “The causal agents of witches’ broom and frosty pod rot of cacao (chocolate, Theobroma cacao) form a new lineage of Marasmiaceae,” Mycologia 97, No. 5, 2005: 1012–22.^

16 More formally, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, adopted 12 December 2015 and effective as of 4 November 2016. Full text.^

14 Global average surface temperatures are projected to rise from a minimum (all emissions stop right now) of 1.0°C up to over 4.0°C (no emissions reduction) by the year 2100. Intergovermental Panel on Climate Change, Fifth Assessment Cycle Report, 2013.^

18 Hannah Furlong, “Hershey, Lindt, Mars, Nestlé Join New Program to Help Cocoa Farmers Adapt to Climate Change,” Sustainable Brands, 2 June 2016.^

No Comments on "The chilling future of chocolate"